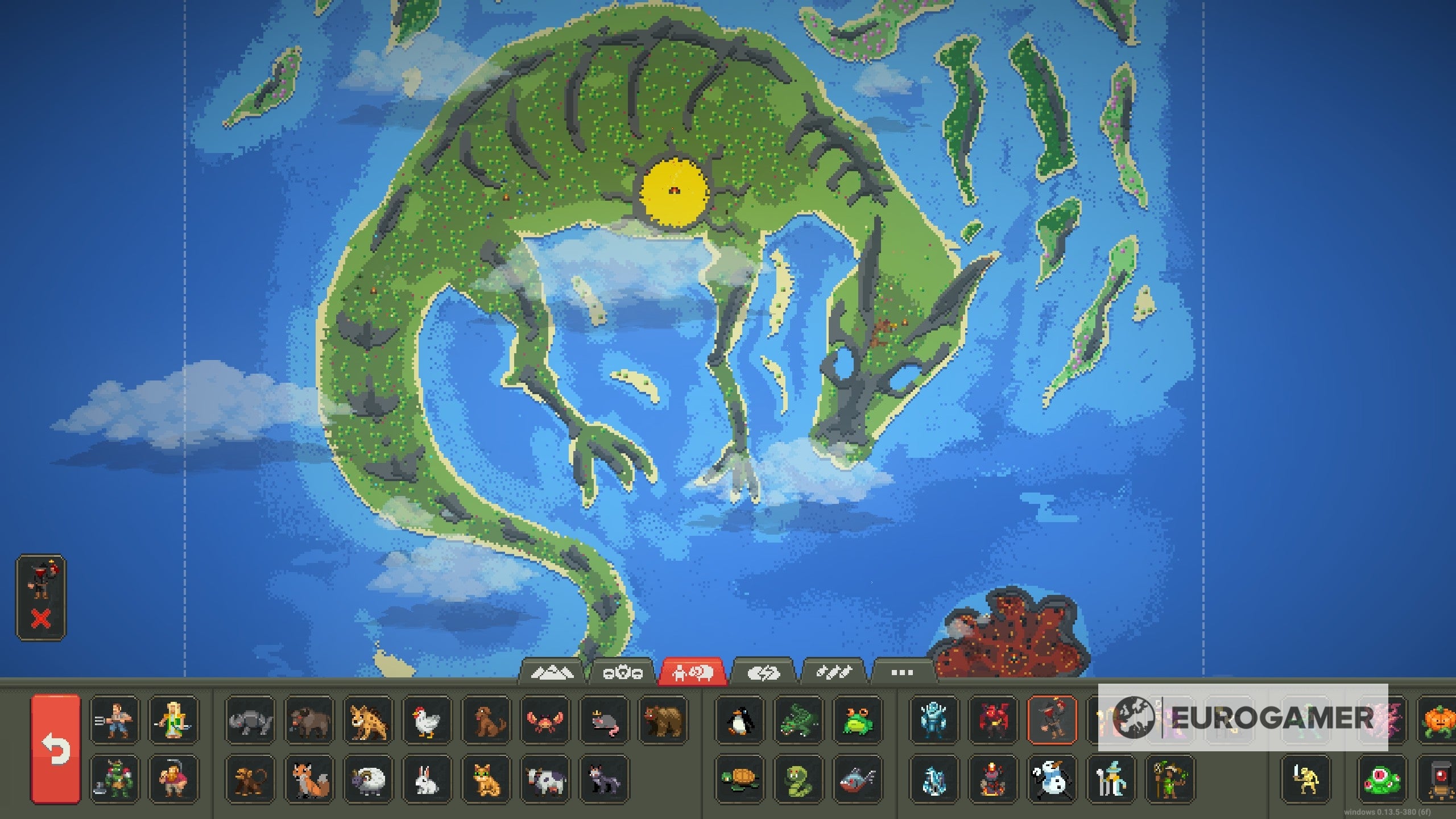

It’s fair to say I have orcs and elves and dwarves on the brain, so you can imagine my surprise when WorldBox let me make, almost literally, a Middle-earth of my own. I even got a ‘well done you’ve made Middle-earth’ achievement when I filled the world with the relevant races. I am, as the title of the game suggests, the god of this world. I can make it look any way I like and then I populate it and see what happens - watch as my races breed and build and spread across my map. All the time they’re doing this, a history is being generated. They crown rulers who age and die. They create kingdoms that prosper and splinter. And, inevitably, they war. And the game tracks all of it, chronicling the history of your world. In my world, the elves ran rampant. They multiplied like a horde of horny Legolases. And they didn’t spread peacefully: they were vicious expansionists, wiping out everything in their reach. I didn’t even notice they’d steamrolled the humans but when they got too close to the dwarves, I panicked. I interfered. But then, what else should a god do? Interfering is the other half of the game. It’s almost as though you establish civilizations precisely so you can interfere, ensuring your test environment is robust enough before you throw challenges in. You try a few wolf packs, bears, rhinos, but since when did any exciting fantasy hinge on mundane encounters like these? Better you reach for the demons that burn the ground in their wake, or the White Walker-like enemies that freeze it. Or the necromancers that summon skeletons, or the evil wizards who are chased around the world by white wizards. Bring any stories to mind? But they are only a fraction of what’s on offer. There are zombies with their notorious infectiousness, there are UFOs, there are dragons. There are natural disasters like tornadoes and earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. There are blessings and healings and plagues and infections. There are even, if you’re feeling particularly destructive, an alarming array of world-killing bombs. And on the other side of it all: many powers of creation, and the ability to regrow and reshape whatever you see. But not, it should be said, the power to control the creatures. You are always strictly hands off. So the game goes: you create (the game also spontaneously creates if you allow it), you monitor (speeding up time if you want), and you tinker. You thin the elves with a tactical demon invasion, or cheekily aid the dwarves with bonus resources if they fall behind. And as you’re doing this, ages or eras in your world naturally begin to emerge. The ages of peaceful expansion or of great wars. The ages when one race prospered as others fell away. The ages when evil swept the land. It all plays before your eyes like ants scuttling back and forth across a garden. But where WorldBox is really clever is in how it pulls you closer by generating detailed statistics for each individual character. It encourages you to inspect them to see character sheets of randomly generated, and evolving, statistics - combat statistics, personality statistics, social statistics. These are living, changing characters in your world. It’s not just the goodies. Check in on a rampaging demon half an hour later and it will have accrued dozens of kills, gone up a few levels, have more hit points and cool new traits like veteran status or only one eye. Check in on one of the kingdom rulers of the world and you’ll see them decked out in rare and legendary equipment forged by their people X number of years ago. Think of the storied weapons from Tolkien’s work, like Orcrist or Glamdring or Anduril - it’s that kind of thing. It’s this personal touch that really warms and colours the broader strokes of the simulation, that gives it a feeling you’re writing a Silmarillion of your own, where great champions and great enemies emerge and battle for the fate of the world. It’s really hard to pull your eyes away from it. Ultimately how complex the simulation is, and how long its outcomes can surprise you for, I don’t know - it’s hard to tell from a few hours of play. But there’s already a lot to play around with, as an early access title with an estimated two-year development journey, there’s plenty of time to add more.