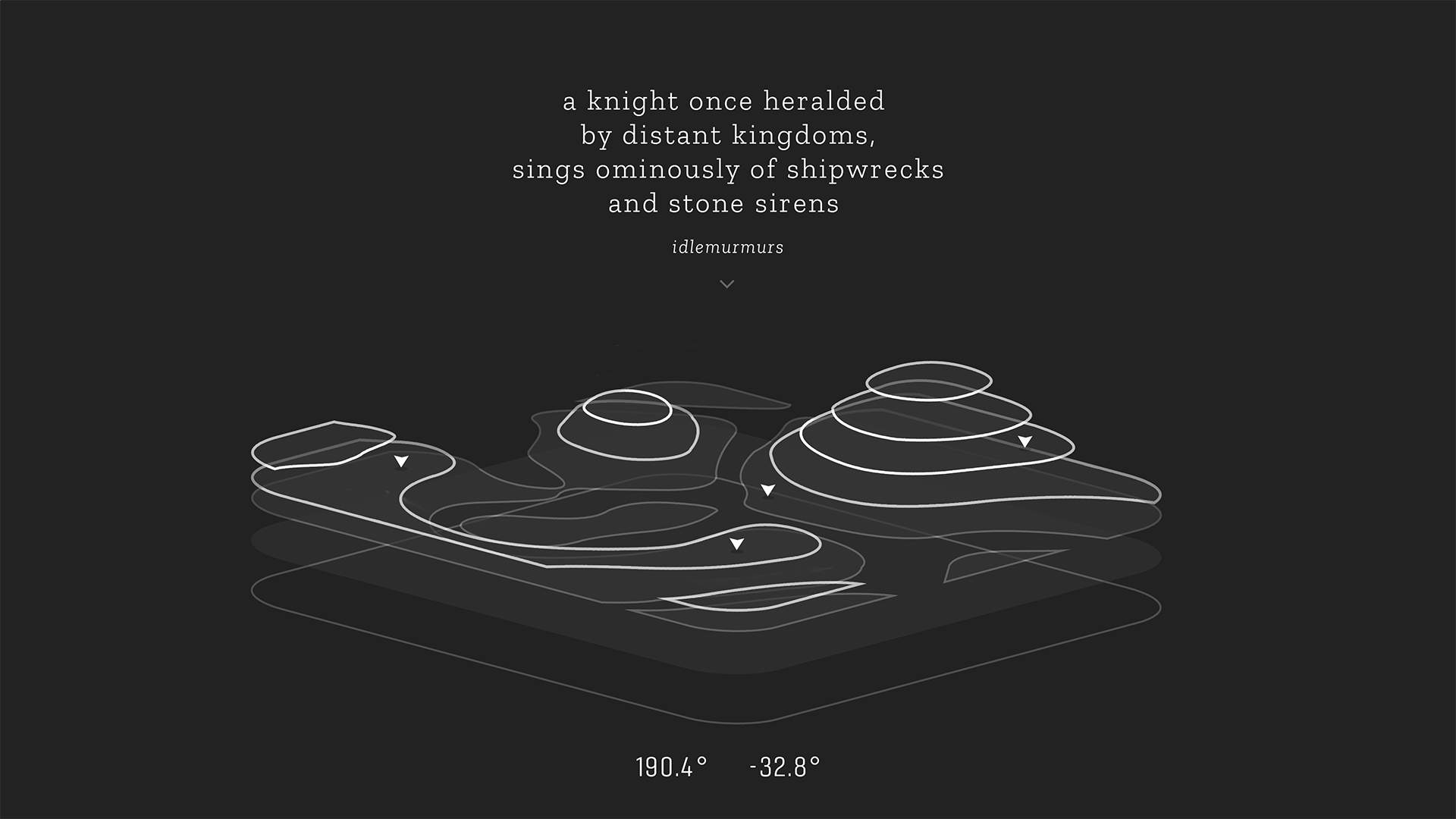

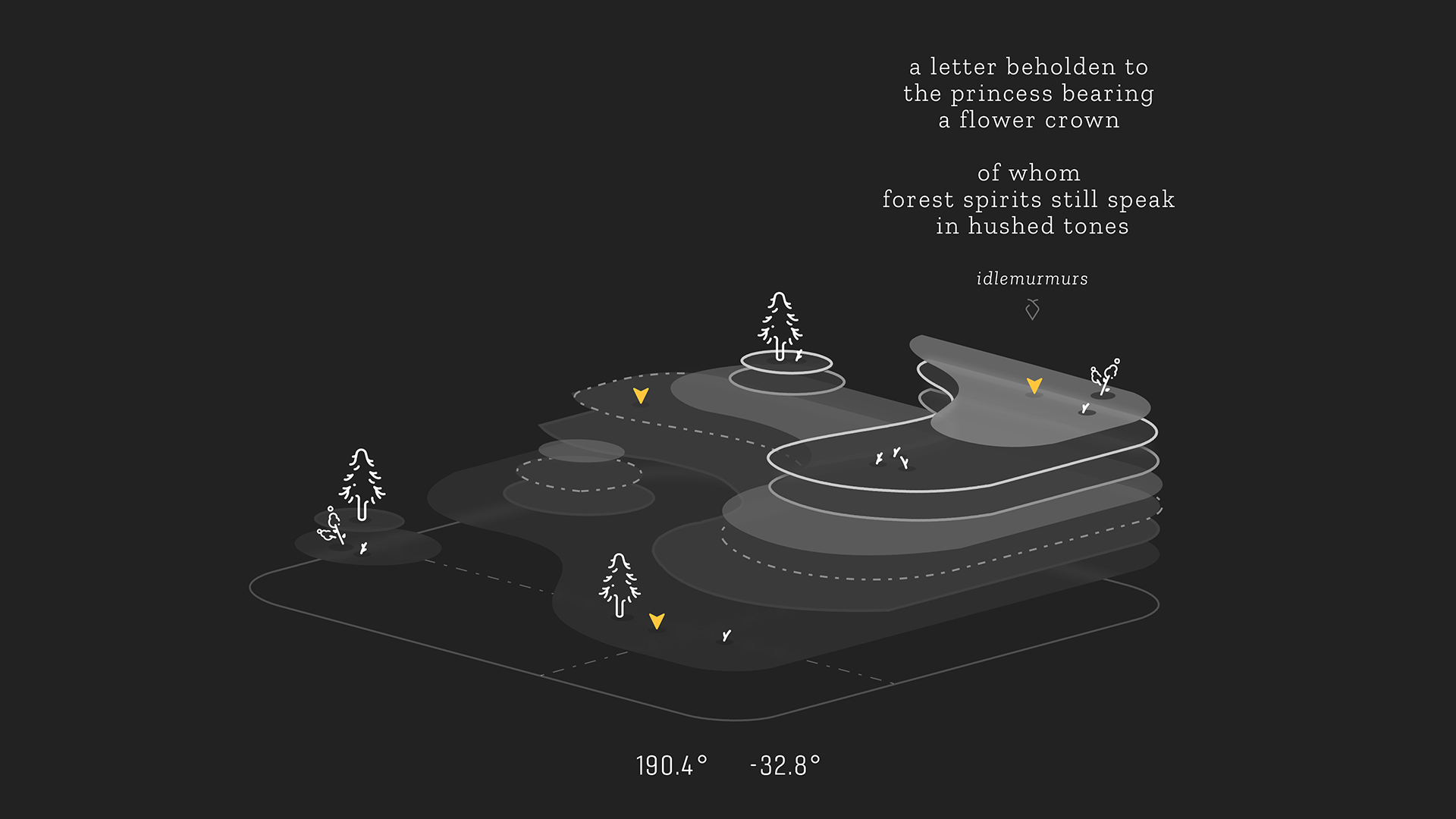

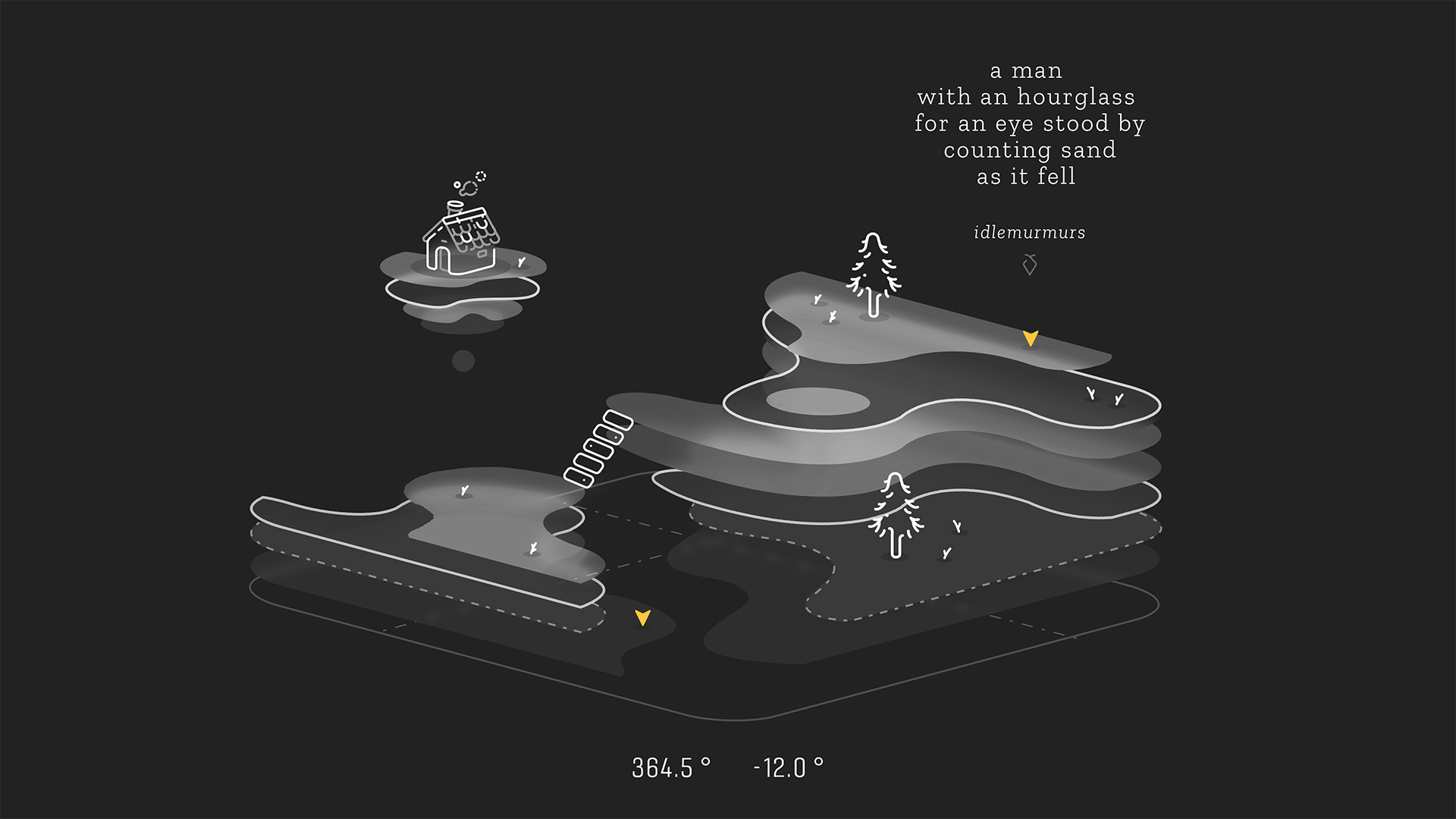

Demi Schänzel is a researcher and game designer from Aotearoa (New Zealand), who advocates for “compassionate design practices and digital kindness.” They are the creator of Library of Babble, one of the most extraordinary digital spaces I have ever explored. In the Library, visitors can read messages from other people and leave their own - and they navigate a shifting landscape of scintillating Miami cocktail colours. It was a real pleasure to chat to Demi last year and learn about how the Library came together. Can you tell me a bit about your background and how you got into making things like Library of Babble? Demi Schänzel: So I feel like, relative to a lot of my peers in the field, I got into game design specifically quite late. You know, early- to mid-20s. And before that point, I was also always terrified of the prospect of programming. I knew I could never be a game designer, at least from this side of things, I think, because I knew I’m hopeless at mathematics and I couldn’t possibly program. But I took a course as an undergraduate, which was sort of an introduction, and found it to be quite light and understandable. It really kind of opened me up to that possibility. And then I spent a few years bouncing around a few different corporations as a UI designer, and mostly did web design for a bunch of web companies and commerce sites. And then a few years ago, I found myself in a position where I was sort of between work. And this offer came up at the university for a scholarship for a postgraduate degree in English and new media. So basically, the study of linguistics on the internet, and software and just how language is emerging online and how it’s changing. And I took them up on the offer. And that’s when I pitched them on the idea of the Library of Babble. You’ve said before that it’s inspired by your early internet memories? Demi Schänzel: Yeah. I mean, I came to the internet quite late. I’m quite young, I’m 27. So my early memories are really like early 2000 internet memories. But I still have this very clear memory of just hopping onto the internet for the first time and just the untold promise of that idea of just being able to go anywhere and discover anything, and just have it all available and for free. You know, just browsing websites and searching things up, not maybe on Google at that point, but Ask Jeeves or something similar. Just kind of seeing what’s out there, I think. And I’ve always really liked that idea. The sort of impenetrable mystery: that no matter how much you find or you discover, there’s always something else. It seems with Library of Babble, you found such an ideal way of representing this landscape in a way that everyone who sees it seems to understand it innately, or emotionally - they understand what the landscape means. Was it quite a challenge to pull that together? Demi Schänzel: I think where it is now, it’s very different from where it started. But I was always really taken by the idea of cartography in a way. We lay out geography two dimensionally. And you have this very beautiful height line. So you have these sort of defined spaces on a map. Wouldn’t it be a really lovely idea if you could get that depth and dimension? So that part of the design came together really quickly. Conceptually, at least - the technical aspects a little longer perhaps. But I always really like the idea of traversing geography not based on landmarks, but just on the sort of granular rise and fall of the landscape itself, I suppose. Did it take a long time to get the feel of it right? I’m always struck by how beautiful it feels to move across Library of Babble. It’s one of the most pleasing games to interact with. That particular floaty scroll feeling must have taken a long time? Demi Schänzel: Oh, it took a long time, I think it was something I was always tinkering with back and forth, you know. And by and large, like, really, throughout the development process, it was more of a case of just making things slower and slower and slower. And just seeing how slow I could really pan things out, you know, in terms of how you move across the landscape and how the interface sort of comes in and out. Seeing how far I could push it, how gradual and slow I can make game while making this experience without leaning into boredom or frustration. There’s a powerful sense of place to the game. Is there a point in the design where you realise - oh, this has turned into an actual place? Demi Schänzel: You know, it’s funny. It happened less during the act of making it, I think. When you’re embroiled in making something, regardless of what it is, it’s sometimes hard to see what it is you’re exactly making, right? Because you’re so involved in the process, you know. So for a really long time, all I saw was all the things that couldn’t fit into the game, or all the things that didn’t work or didn’t quite work the way I wanted them to, especially in the last year and a half. Every time I’ve gone back, though, I do kind of get that feeling. Now that the memories of creation have faded now. And now I just kept this kind of this space that now feels whole and complete, that it’s no longer composed of things I can put into it, rather just… You get a chance to see what you’ve actually done? Demi Schänzel: Yeah, truly. Just before the interview, I actually booted it up, you know, for the first time in six months or so. And it’s a really touching feeling. Enough time is now passed where it’s: oh, I can see how other people perceive this now. It’s no longer from a completely internal perspective. And that was really special. Because that was what I was going to ask you: What is your relationship with it now, and with the community that it has created? How do you feel when you return to? I think you’ve answered that to be honest. Demi Schänzel: It’s something I’ve really been struggling to put into words. I think it’s a very rare thing to make a game or anything, really, to put it out in the world and to be able to return to it not as the author but perhaps as a reader. And I think a large part of that is now there. So much of what the game is now is composed of what other people have put there. To me, it almost feels like the actual thing I contributed was the small space in the game itself and that’s the smallest part of what it is, you know. So it’s a really touching special feeling. Are people still adding things to it? Demi Schänzel: Yeah, a few messages here and there each week and it’s slowed down a lot. But it’s nice. What kind of place do you think it is for the people who write there? Demi Schänzel: Yeah, I’m not too sure. I mean, I will say when I released it, I really wasn’t sure what to anticipate at all. I think language on the internet and how we write on the internet, how we converse, there’s such a sort of fixed cadence to it now. So I was really worried at the time that would it be just trolls and very non-committal messages? I really did imagine it initially as a space to tell stories. And that’s kind of what I anticipated is for people to sort of write these stories - make-believe fables and such. And now what I found is like, it’s an incredibly intimate and tender space. Like, I don’t think I’ve ever seen writing quite like this laid out on the internet before. And that’s a really special feeling. I think. It feels like a very vulnerable space. So finally, what are you up to now? Are you thinking about what’s next? Demi Schänzel: A little bit. You know, I really still adore the notion of space and conversation. Every time I go back to that year, and sort of try to revisit what the core experience of the Library of Babble is, I don’t know how to change it, or what to make without creating something profoundly different. I think it really works most beautifully in its most abstract. And as soon as I sort of try to recreate experiences that are that are a little more focused on landscape and geography and as such, it also falls apart a little bit. It sort of becomes embodied its own narrative a little too much, and doesn’t really allow for that same sort of level of self-expression. But I am working on a small thing - I suppose you could sort of imagine it as a chat room, just a really, really small space, a seaside cafe thing entered via a train. And you have the opportunity to meet about four or five strangers and just sort of exist in the space and talk with them. And that’s something I’m sort of experimenting with at the moment. I like the kind of thing of being able to meet other people in settings outside of ourselves, you know, sort of allow for moments of intimacy and vulnerability. Purely because it is anonymous, there’s no way to identify someone else, and there’s no way for them to identify you. I think this sometimes opens us up to be allowed to have conversations that we can leave out there in the wild, knowing there won’t be some sort of long-term repercussions.