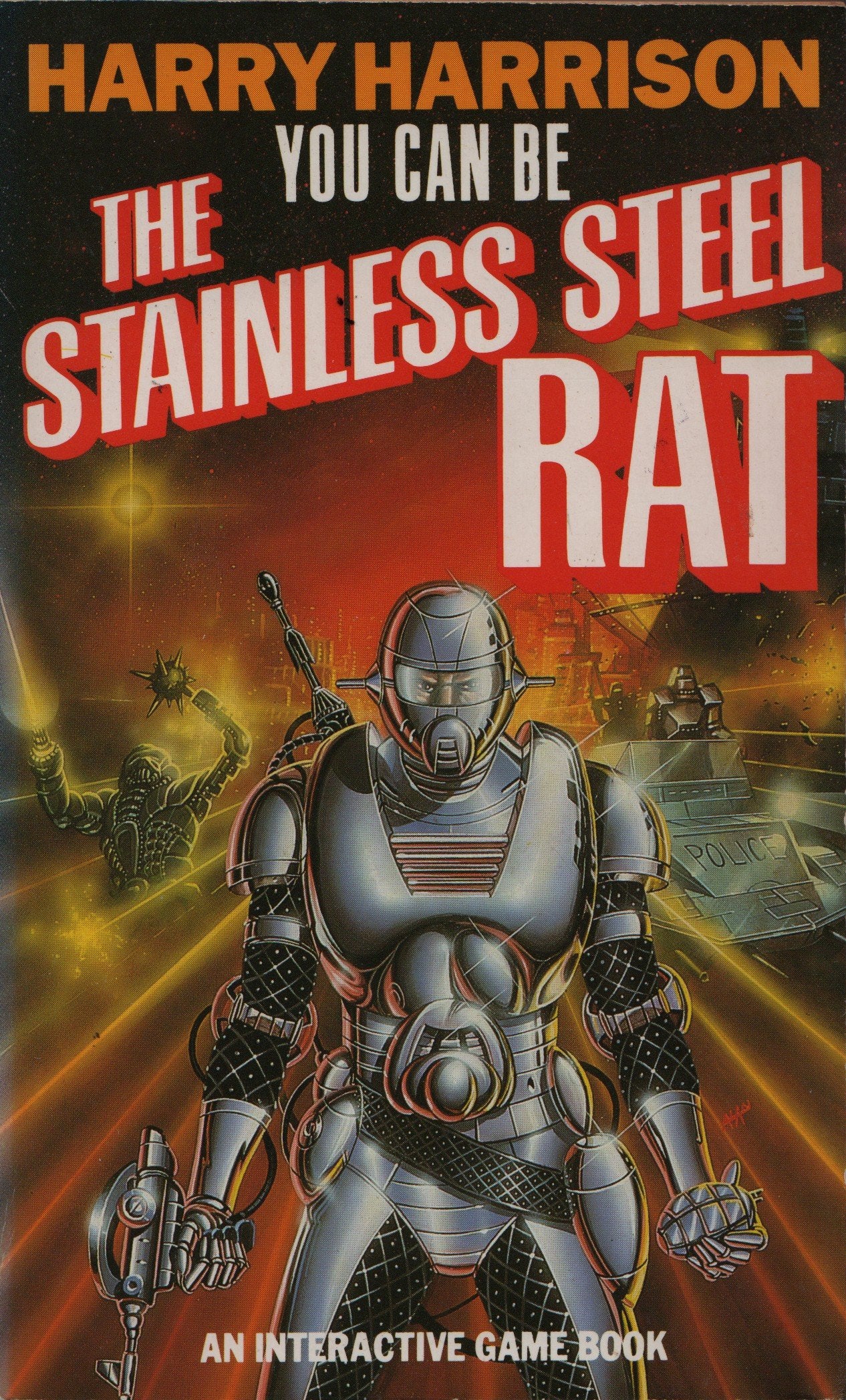

Actually, it was a very special one, an odd one. But we’ll get to that in a second. Harry Harrison was a big deal in 20th century sci-fi, a writer who moved from illustrating comics to turning out novels that existed in the raggedy edge-lands between parodying space operas and reveling in their excesses. However he handled things, he always brought an anti-war message that was sometimes hidden, given the rather conservative genre he worked within. Outside of the Stainless Steel Rat books - the Rat is a charming con-man and occasional hero - he’s probably best known for writing the novel that Soylent Green was loosely based upon. So yes, the book of Paul’s I’d found was a bit of an oddity amongst Harrison’s output. It was a game book. You Can Be The Stainless Steel Rat was published in 1985, according to my lovely eBay copy, battered but still with a bit of gloss on the cover. 1985! This means it hit right in the middle of the Choose Your Own Adventure craze, and it cleaves tight to many of the genre’s standards, like numbered sections that come with choices at the end. As a reader, you ping back and forth through the book following your instincts, and probably keeping a finger or two marking previous choices for the moments in which your instincts fail. I have no idea why I started to read this book back then - other than I would have been very young, and the whole thing struck me as being pleasantly illicit. A book aimed at teenagers, at least, with a cover that promised easy access to carnage. That would have been enough for me. I can certainly remember why I kept reading, though: far from going over my head - although I’m sure some of it did - the book was charming and light, and the action, narrated by the Rat himself was often funny. The Rat didn’t just describe the scenes and the choices the reader faced, he commented on their actions, and specifically their many failures. When the reader gets hit on the head for about the thirtieth time, the Rat asks whether they are secretly getting something out of it. When the reader makes a risky choice, he tells them how stupid they are, and sometimes gives them a second chance to make a better decision. I love Choose Your Own Adventures, and for whatever reason, a few days back I found myself filled with a desire to return to this formative example. Days later, I had the book again, looking at that beautifully garish cover for the first time in at least thirty years. I’ve spent the last few hours re-reading and re-re-reading. And it’s fascinating stuff. Fascinating how? As a Choose Your Own Adventure affair goes, the story is hardly a reach. You’re dispatched to an awful, dangerous planet to track down and capture a scientist who has manufactured a doomsday device. Along the way you meet deadly enemy agents, intriguing allies and a couple of monsters - standard stuff for these kinds of books. You have gadgets - smoke and gas bombs, an invisibility belt - but it’s all tracked within the pages of the narrative with no need to write up a character sheet. You don’t need dice, either, although occasionally you’re asked to flip a coin. But within this traditional genre mount, I think you get to see something pretty special - something I hadn’t noticed, for obvious reasons, on my first, all but forgotten playthrough back in the 1980s. It’s this. Harrison takes his job seriously, up to a point. Numbered paragraphs. Choices. An adventure plot. But beyond that point you get to see him - what? Bored? Playful? A combination of the two? I first noticed this early on, when the choice at the end of a section came down to something less commonly seen in these sorts of books than the question of whether I should go left or right at the next intersection. Instead, the Rat had remembered a few lines of a poem, and he wanted me to tell him: Frost or Service? It was Frost, but that’s not really the point - the point was that I had to pick an answer and turn to the correct section to continue the story. Bored or playful? Was Harrison simply fulfilling the obligation to make the reader choose, or riffing on that in an interesting way? In a book about making choices, why shouldn’t some of those choices play out in the privileged inner space of memory and thought anyway? There’s lots of stuff like this. Not poetry, but bits where you can see Harrison pushing against the boundaries of the form. He tells the reader to learn Esperanto at one point - a bit of a Harrison preoccupation. Elsewhere he becomes enormously fond of the choice that is not a choice: you pick an answer, and he sends you back where you came from anyway to pick the other option. Along the way, I think Harrison makes a really interesting discovery. Death in Choose Your Own Adventure books is interesting, I would argue, only if the book is actually crafting a range of radically different stories - in which case, each death is actually an ending to a story, and stories with endings are great! Take something like the old Choose Your Own Adventure The Horror of High Ridge and you’ll see exactly what I mean. High Ridge is a story of ghost cowboys and Native Americans fighting over an old mining town. But as you pick through the book, the scenario gives way to many plots: in some you get killed by evil cowboys. In another you flee the town, or die fleeing in yet another. In one plot - a sort of master plot - you actually put an end to the ghostly curse on the town. There’s a lot of reader death in High Ridge - it’s something the books used to advertise on the covers. But actually what they advertise is endings rather than deaths. Many endings are deaths, but more than anything they bring a story to a satisfying conclusion, and allow a single book to contain several largely distinct narratives. A lot of times in game books, this wasn’t the case - or at least I don’t remember it being the case. You might lose a fight and just die. You might trigger a one-hit trap and that was it. The story would end with no meaningful form, no pay-off, crafted or accidental. It would be abrupt and a bit pointless. Harrison gets around this quite simply. I don’t think you can even die in this book. I’ve been playing for a while, and I haven’t died yet. Instead, what happens - and this is sort of brilliant really - is you get lost instead. Harrison loves to create loops - sections that can ping you back and forth between the same handful of numbered paragraphs unless you’re careful, unless you’re attentive. There is a thrill here: it’s the literary equivalent of an optical illusion, I think, that Harrison could create so many sections that worked regardless of the order that they’re read in. There’s also something quietly instructive. You get stuck in one of these paragraph mazes when you’ve ceased to focus. It reminds me very strongly of the Doldrums in The Phantom Tollbooth, which is not a game book even though it can feel like one. The Doldrums are grey, misty areas of twisting, looping roads, that you find yourself trapped within whenever you haven’t been paying attention. So: playful or bored? I am tempted to say playful for the most part. Harrison may be experimenting with an odd new form, but this is a guy who had started out illustrating comics, so you like to think hopping between one form and another would bring out the best in him. On top of that, the action sequences here, which often involve lightning fast choices, short paragraphs and surprisingly tricky decisions, really race along with an expert pelt. There is a passion for adventure and fun driving these parts of the book, a desire to match the reader’s paging back and forth for the next section with a hectic, Looney-Tunes kind of action. Then there’s just the fact that Harrison throws some neat stuff into the book - I’m particularly fond of an evil guard who is so hardcore he’s stitched his seargent’s stripes onto his skin rather than his uniform. I don’t think a writer would waste an idea like that on something he wasn’t at least somewhat into. Two final things. Firstly, Choose Your Own Adventure type books are brilliant fun to read as an adult because you get to see a literary form evolving at an incredibly fast pace - for a while, almost every new book would build on a good idea from elsewhere, jettison stuff that had ceased to work, and throw in something entirely new just to see what would happen. The readership was shaping the genre one new book to the next, and it could be a bit like watching one of those summer storm clouds gather and darken and erupt over the course of a few minutes. Secondly, Harrison died in Brighton back in 2012, and I remember that because I almost got to meet him once. A friend of mine was part of an informal pub gathering of sci-fi writers and fans, and Harrison used to come to their meetings - I think he was something of a hero to them all. I went along on a few occasions and found a quietly magical environment largely composed of knackered secondary school English teachers. The kind of place where you could make new friends, eat a free packet of crisps, and get into a serious argument about Tim Powers, if you weren’t careful. I never turned up when Harrison was there, though, and then one day I read online that he had died. If I had met him, with the benefit of this week’s re-reading, I think I would have said: thank you. Thank you for having fun with a lovely oddball genre, and thank you for taking it seriously, even as you had fun.