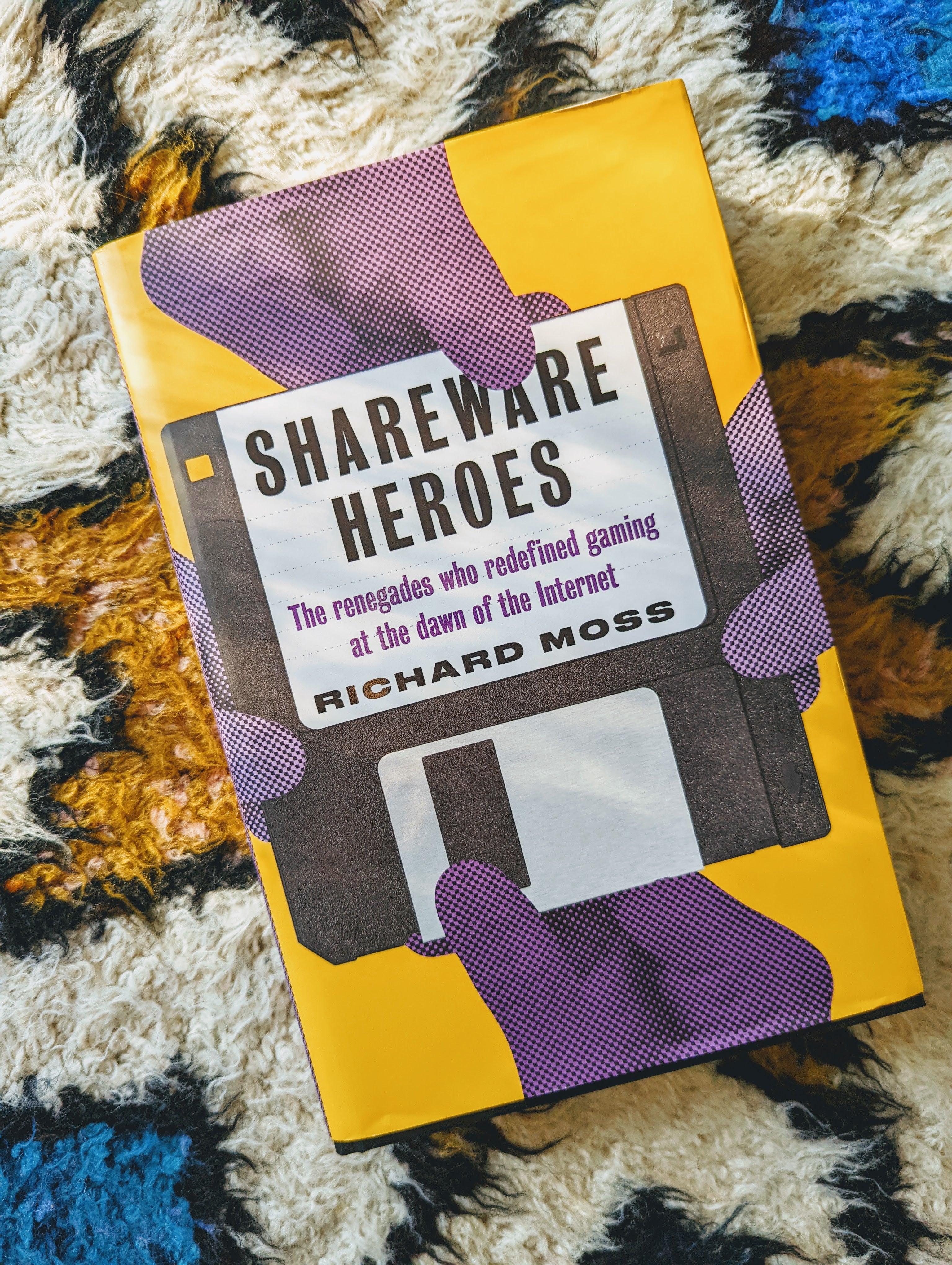

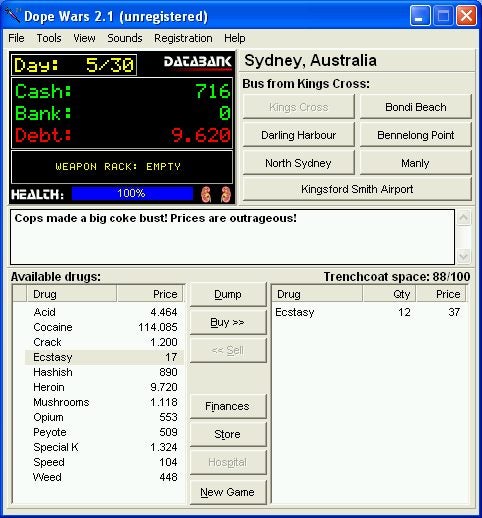

But that was shareware: finding stuff for free. Or, at least, that’s what it represented to me - I now realise I might have been part of the problem. But I was a teenager! I was broke. That’s why I got sucked into Dope Wars with all of my other MSN Messenger buddies in 1998, buying and selling drugs at very competitive market prices (in a game!), and how I found an RPG called Dink Smallwood, which I remember vividly to this day. Does anyone else? I’m genuinely curious. Really, though, shareware began a long, long time ago, though it can still be seen today (whisper it: “freemium”). And I learnt this from a new book called Shareware Heroes, written by Richard Moss. It attempts the daunting task of presenting a history of shareware by telling the stories of all the people involved in it. That’s the equivalent of trying to follow all the separate threads in a bowl of spaghetti. But Moss, admirably, manages it. He charts the origins of shareware in the ’70s and how the movement got its name through a magazine poll in InfoWorld - apparently one of the strong contenders was “conscience wear”, because the longer you used the software, the more it would wear on your conscience that you should pay for it, which sums up the idea of shareware nicely. But games struggled to make any money from it, early on, apparently. It was mostly word processing and other utilities making money back then. It wasn’t until a motivated fellow called Scot Miller came along and created Apogee, and an idea of breaking a game into three parts, one of which you could have for free, the other two you’d have to pay for, that things began to take off. His Kingdoms of Kroz games, released in ‘87, earned an unheard of $80,000-$100,000 at the time. It was off the back of this success Miller started to look for people he could collaborate with, and his search led him to John Romero and what would become the legendary id Software team. And there’s the wonderful story of how Miller had to be careful about approaching Romero to pitch him, because Romero was already working at SoftDisk making games. Miller’s plan was to write fan mail to Romero under a pseudonym, to try and coax him to contact him. Miller would tell Romero he loved his games but he’d spotted some kind of bug so please can he call or write him back. Yours, “Scott Mulliere”. Romero received a few of these. It wasn’t until he was reading an article about Apogee and saw the business address at the end of it that his mind sounded an alarm and he realised what was going on. And he wasn’t happy, but the two got to talking and a deal was made. That deal changed everything. It would lead to the Commander Keen series, Wolfenstein 3D and eventually Doom, all released as shareware. And each one shook the industry like an earthquake, until Doom took id Software and shareware and gaming mainstream. The other major throughline is Epic Games - or as it was originally called, Epic MegaGames. Tim Sweeney founded and grew that company through shareware, though his idea revolved more around giving people a platform to get games on and make content for, and eventually an engine they could build games with - an idea not a million miles away from what Epic is still doing with the Epic Games Store, Fortnite and Unreal Engine today. But those are the big stories. Equally important to author Moss, and to the shareware movement, are the many other stories about the many other people involved. Shareware, really, was infinite. It didn’t belong to anyone; therefore, it belonged to everyone. There were no rules, no owners, and that was the fundamental pull of it. Shareware was freedom: a way for people to release things without interference. That’s how the world got probably the first game about LGBTQ+ themes: Caper in the Castro, released in 1989 by non-binary transgender creator C.M. Ralph, to raise awareness and, eventually, money for the AIDs epidemic. The game was about a lesbian detective searching for a drag queen friend, and instead of ask people to pay for it, Ralph asked for a donation to an AIDs charity of the player’s choice instead. And when someone took a disc of the game on a business trip to the UK, the game spread there and around Europe too. Hundreds of thousands of people downloaded the game. That’s the power of shareware. And that, really, is why “shareware” will mean so many different things to so many people. To me, it’s Duke Nukem 3D and Dope Wars and Dink Smallwood (which was “freeware”, technically, but shh) but to you it will be something else. And even if you’ve never seen the label “shareware”, you’ve felt the repercussions of it - you’ve played the demos, tried the free-to-play games. The legacy of shareware is everywhere.