Thirty years after a war over salt, a resource held entirely by Hyzante, the treaty is meant to re-establish both diplomatic relations and trade between the regions, even as salt itself is still jealously guarded. Of course it all plays out very differently. The steadfast Serenoa, loyal to his crown and the people of the Wolffort region both, soon turns out to be less than perfect - and is actually just barely equipped for the many difficult decisions he has to make.

In how it approaches war, Triangle Strategy takes some heavy inspiration from Yasumi Matsuno, the creator of both the Ogre Battle series and Final Fantasy Tactics. Just like Tactics, Triangle Strategy explores the justifications for a medieval society’s battle for resources, and the effects of it all - with all the Game of Thrones-style political scheming that comes with it, too.

The battles themselves are a highlight, but also surprisingly rare, which creates a slightly odd imbalance between those and its hefty story. It makes sense to not have a battle every few minutes, but since combat is often a lot more engaging than simply watching Triangle Strategy’s many cutscenes of diplomatic discussion, I could have done with more of it.

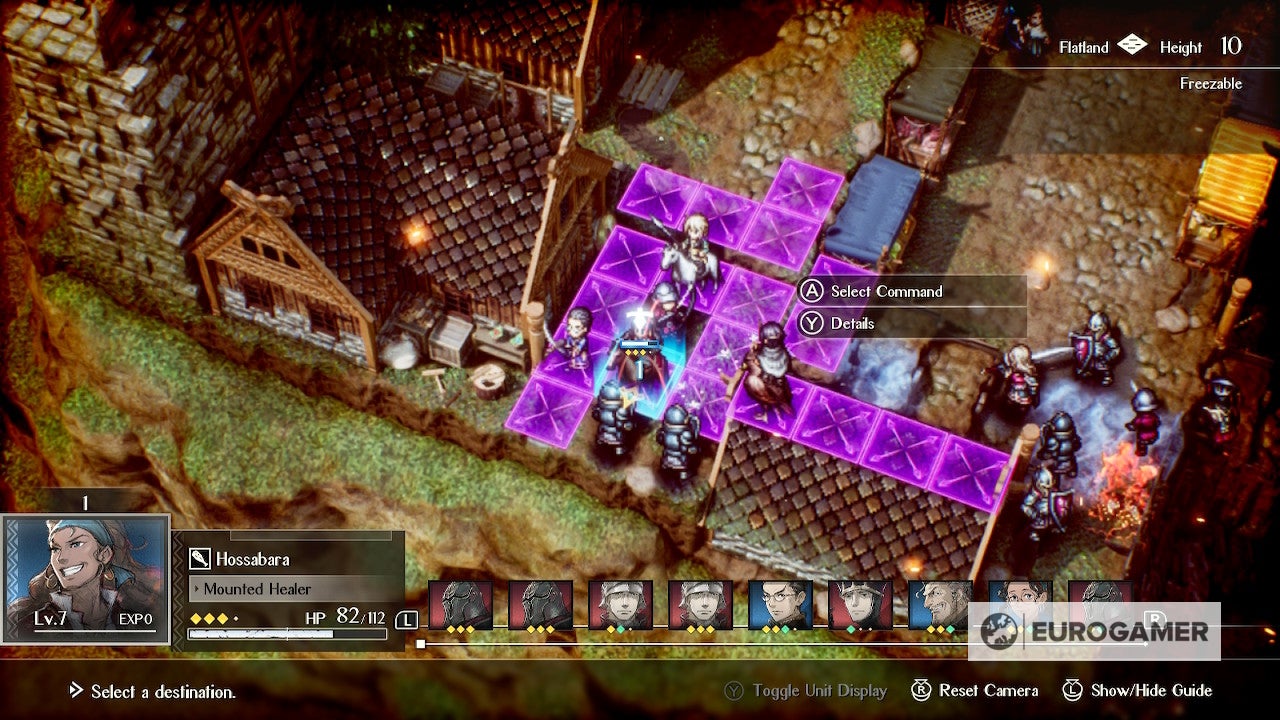

Still, they work well. The turn-based battles take place on an isometric grid. In each turn, a character can both move and take an action. At the end of each round you also have to decide where a character should be facing, seeing as any attack from behind constitutes an automatic critical hit, and flanking a character allows for follow-up attacks with often devastating consequences.

Meanwhile, certain actions, such as special attacks and magic, cost TP. Characters have set movement ranges and attributes - Prince Roland of Glenbrook, mounted on his horse, can move quite far and attack several enemies in a straight line with his lance, for instance, while heavy-set knight Erador can take more hits than most and pushes foes away with his shield.

The maps also frequently involve obstacles and elevation that, while not providing cover the way they do in the XCOM games, for example, can still be used to your advantage, and this interplay - between each character’s unique attributes, the ever-scarce TP points and some outstanding map design - means combat is excellent, often leading me to take a good hour per encounter. Tactics RPGS flourish in situations that force you to take a step back and think: can I move my healer close enough to a wounded party member in time? Should I launch a ranged spell now or save my TP in case it could hit even more enemies the next round? Triangle Strategy absolutely delivers on that.

It’s also reliably challenging - challenging enough for Square Enix and Artdink to add several difficulty options and remove permadeath, following feedback from the first demo. But it remains fair: losing a battle will still award you with experience points and the option to try again.

Because the campaign has so few encounters, getting your characters to the recommended level also involves taking on mental mock battles available at your encampment. Here you get to try a few scenarios not otherwise available as part of the story and earn additional experience. It’s a great way to level characters you may not have used enough, as only the characters in your active party earn experience, and also a good way to simply try out their abilities.

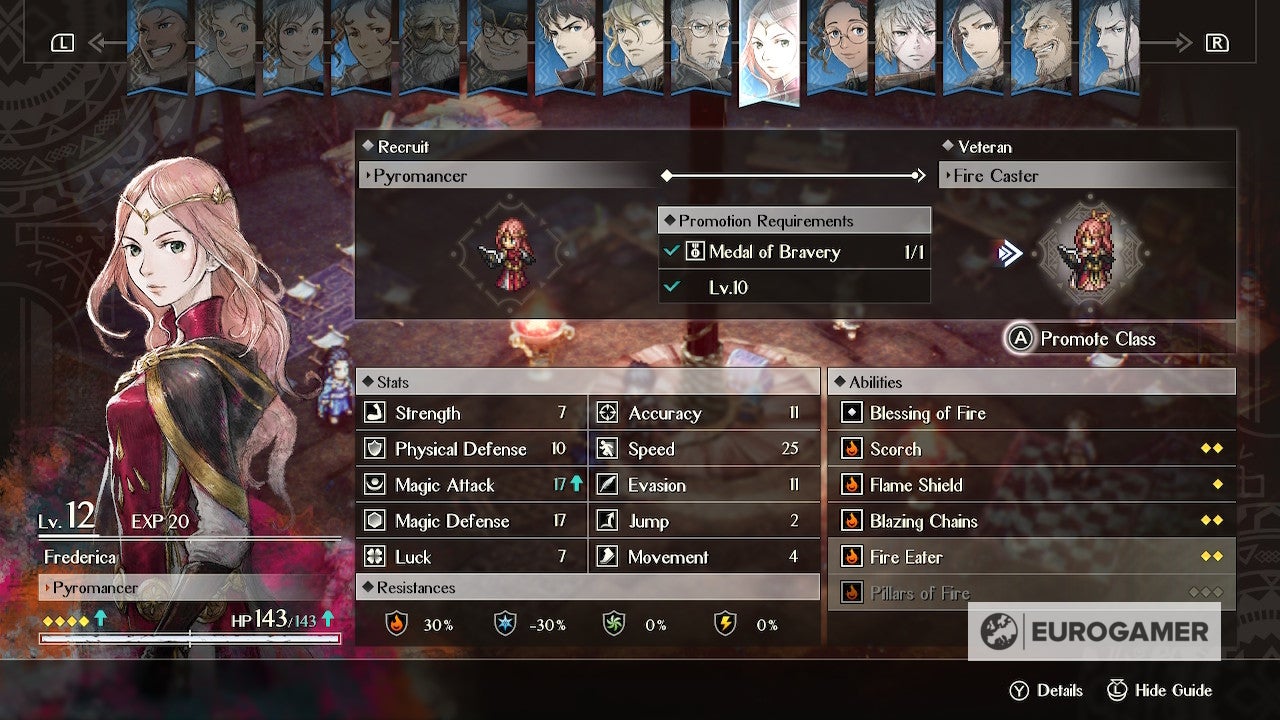

This matters because Triangle Strategy has so many playable characters. So many that I’ve not been able to unlock all of them in one playthrough, in fact, which is likely deliberate (incidentally, the system deciding when you unlock someone and who it is works invisibly). Each character has a unique ability, which is an amount of variety I’m frankly fascinated by. That said, it becomes difficult to manage from a certain roster size onwards. I will admit there are characters I’ve never used during the first playthrough just due to the effort it took to level them, but Triangle Strategy is no different than Fire Emblem in that regard.

Range is nice, but the characters in Triangle Strategy could have used more clearly defined personalities. As it stands they often feel like stand-ins for arguments or demographics rather than individuals. I know next to nothing about some of them, even though I’ve unlocked some optional side stories. I would’ve loved something a bit more involved, but this - plus the fluctuating quality of the English voice-over (a Japanese option is available) and the fact that Triangle Strategy only shows its beautiful character art in menus - is my only complaint when it comes to them.

The campaign alternates between cutscenes, battles, exploration and decision-making sequences, and the distribution of time between each of those aspects is where Triangle Strategy can get tedious. A battle is often followed by over an hour of cutscenes. You do regularly get thrown back onto the world map - in case all this listening to the story has got you tired and you would like to play a mental mock battle or two - which definitely helps, but I’ve played visual novels that involved their players more heavily than Triangle Strategy.

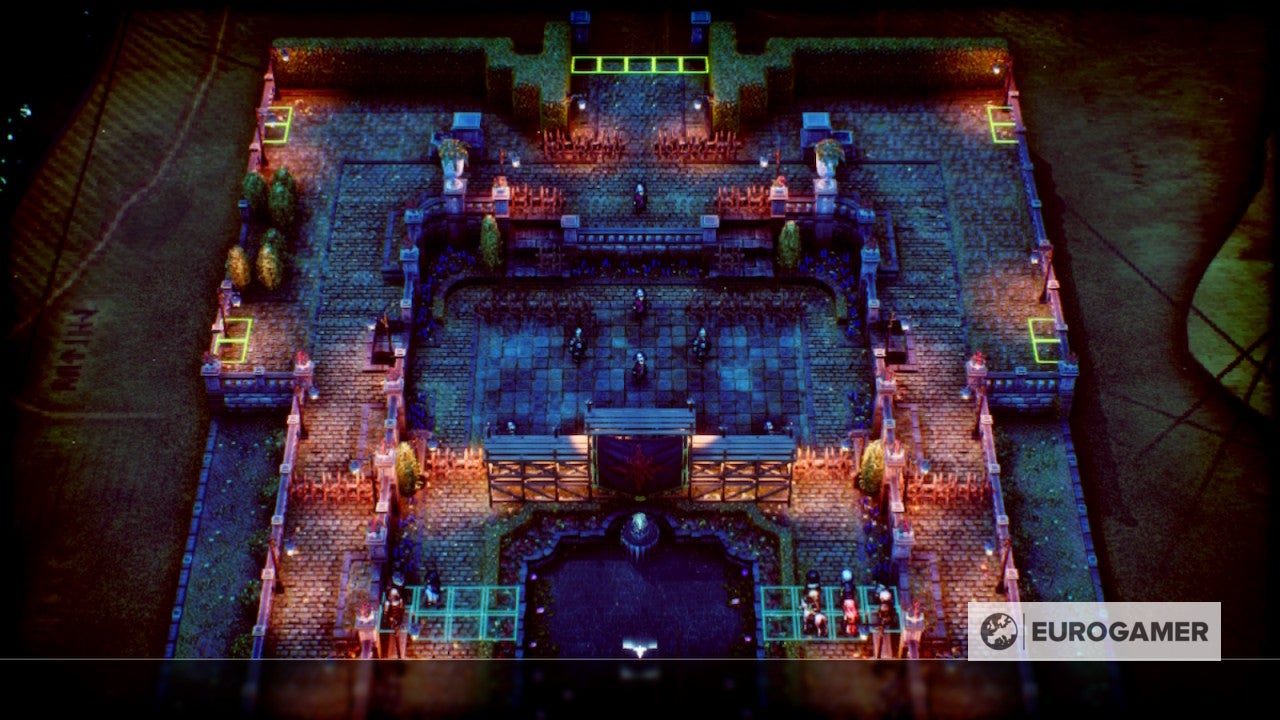

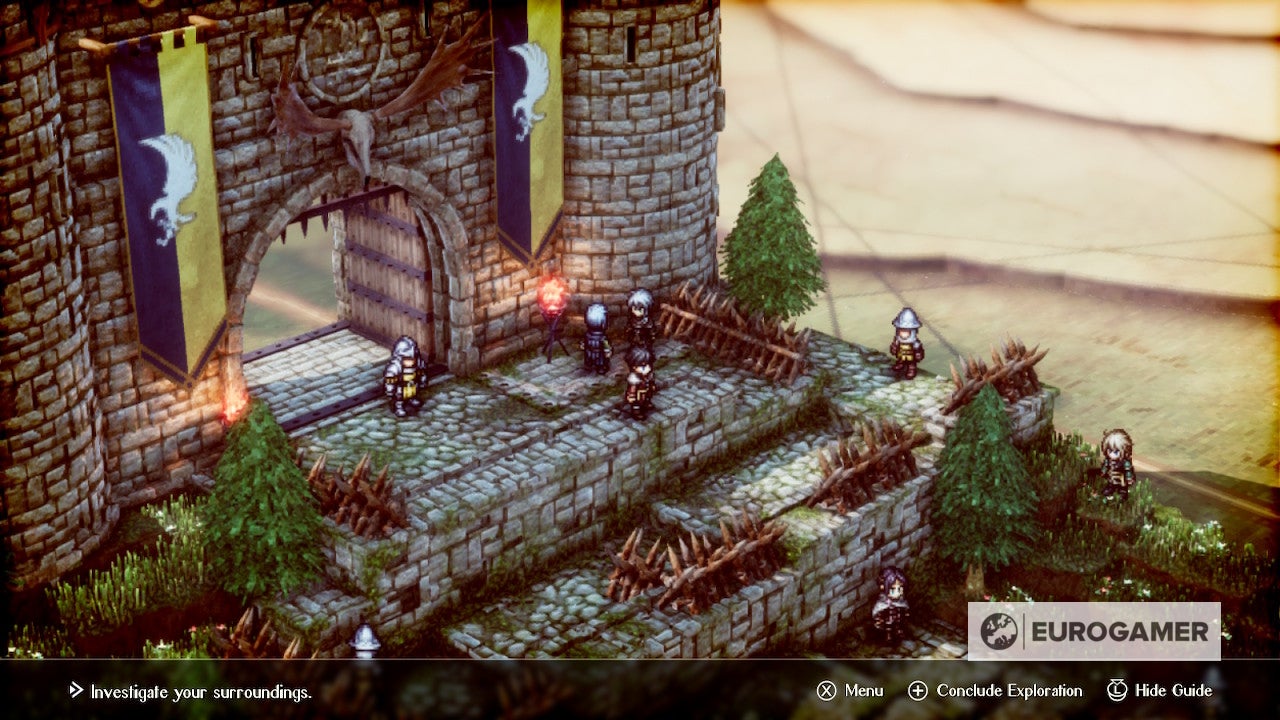

Between the action, exploration sequences let you move around a small location as Serenoa; here you can collect some items and talk to your companions during quiet moments before battle, or scoping out a future battleground. These scenes are nice opportunities to take in Triangle Strategy’s beautiful 2D-HD style, a mix of 3D and 16-bit elements similar to Octopath Traveller. Lighting effects such as fire and lightning look beautiful, the air is often heavy with little dust motes, pools of water glitter in the light and grass sways softly. The environments look like small dioramas with the way you can always see their borders, and seeing 16 bit characters in such a game is a simple, nostalgic delight, often bringing to mind the game’s spiritual predecessors.

Following battles, I’ve also spent a lot of time in levelling menus. In Triangle Strategy, you level weapons and characters individually. Both methods broadly influence the same stats, but character levelling is rare and involves a special item (think Fire Emblem: Three Houses), while in weapon levelling you can use materials such as timber and stone to upgrade specific stats such as HP, which will differ for each character. Notably though, you’ll never have enough resources to upgrade everyone, both due to the cost of material and the cost of upgrades rising each time you unlock one. It’s a system that takes time getting used to, but you can further differentiate characters this way, making two spell casters feel completely different even though their starting stats are broadly the same.

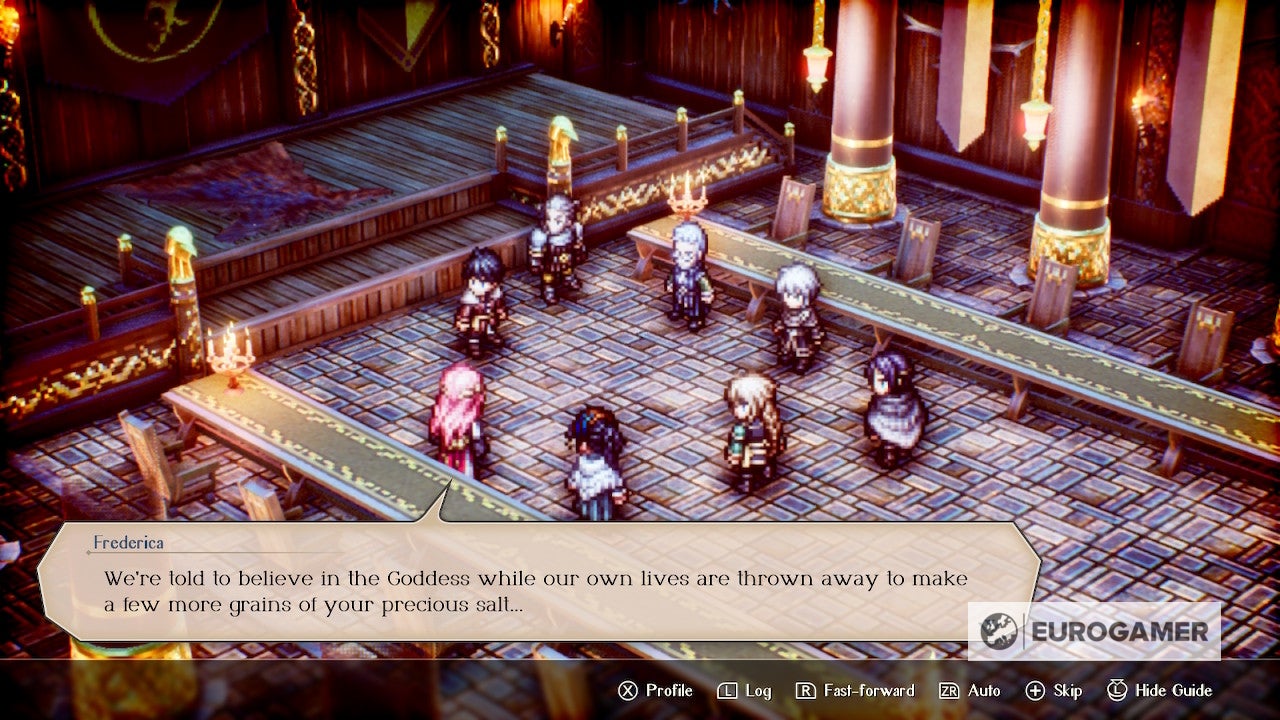

On the topic of choice, sometimes events in the story will necessitate a decision to be made. In these cases, Serenoa will bring out the Scales of Conviction. His retainers will suggest and discuss several courses of action, and you have to try and persuade each of them of your chosen option. Then a vote will take place and the story will mildly diverge in response.

One example: the first decision involves whether Serenoa should go on a diplomatic mission to Hyzante or to Aesfrost. Most of these decisions don’t have an immediate influence on the overall story, meaning they’re not being referenced when the story converges again. Still, they offer different viewpoints on events and also offer a reason to replay the game beyond finding every character and chasing the big goal of finding the three endings.

They also remain a highlight thanks to some stand-out writing. I’ve played a lot of games that ask you to make decisions with the story, but Triangle Strategy’s take on the mechanic is fascinating. The decisions are all weighty, clearly with a lot of thought put into their ramifications. In one instance, I’m being asked whether or not to sacrifice part of a town to keep the enemy at bay, elsewhere I’m asked whether or not to ally with a potential enemy. Each of your retainers has an opinion, and there are no easily discernible ways to change their minds.

Sometimes, additional information gained during exploration can make the difference in getting someone to your side of the argument, sometimes not. The fact I pored over each of these decisions and the follow-up discussions they inspired, rather than picking between a nice option and an aggressive option as other games would have me do, is worth so much from a narrative standpoint.

That makes it even more of a shame whenTriangle Strategy, for all its thought and elegance, reveals some events entirely too early, but overall it does a great job of showing how war is a complex issue, and the ways it impacts the general populace, trade, and, since this is a medieval setting, more nebulous concepts such as honour and loyalty. Triangle Strategy even talks about slavery in a measured way without resorting to modern racial allegories, which elsewhere often come out stilted when translated back to fantasy worlds.

I also find it fascinating that none of Triangle Strategy’s endings are “good”. While things come to a hard end for you as the player - after 36 hours for the first playthrough in my case - the work of governing a people is never done, and there is never a perfect way to do it. This is a divisive thing to settle on for a fantasy game, as my first reaction as a player so used to some degree of winning was honestly mild disappointment. But the game is better for it. As a result of all this, despite its often glacial pace, Triangle Strategy is a dramatic, often engrossing tale of medieval conflict - and one that can sit proudly next to the games that inspired it.